I mentioned in yesterday’s post that, despite having visited my godparents in East Grinstead numerous times, I knew little about the town itself. Thanks to its brilliant Museum, I’ve managed to right some wrongs – and what I learned in the second half of my visit, at its ‘Rebuilding Bodies & Souls’ exhibition, bowled me over.

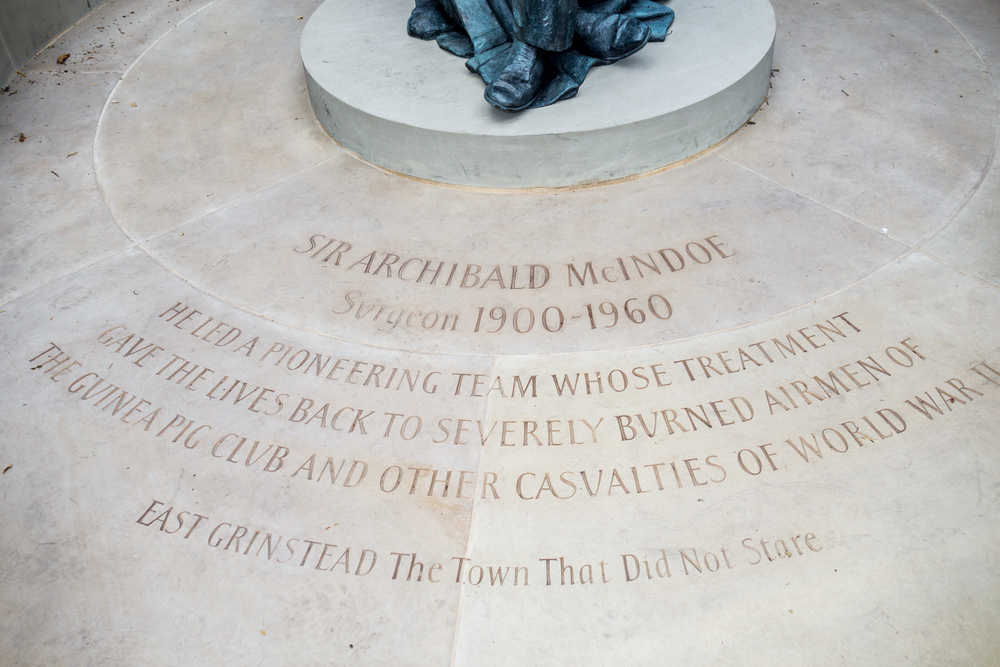

East Grinstead has long retained a place in British medical history. Its first hospital, opened in 1863, was swiftly followed by two more. In the late 1930s, its Queen Victoria Hospital became one of four specialist Emergency Medical Service Units designated to deal with burns casualties from aerial combat and air raids during World War II. On 4 September 1939, a Mr Archibald McIndoe, Civilian Consultant in Plastic Surgery to the Royal Air Force, arrived to run its new Centre for Plastic and Jaw Surgery.

Just who was this esteemed gentleman who pioneered plastic surgery and had such a profound effect on so many lives? Archibald McIndoe was born in New Zealand in 1900 and studied at the University of Otago Medical School. In 1930, he emigrated to London to work in the Plastic Surgery department at St Bartholomew’s Hospital. Following stints at the Chelsea Hospital for Women, St Andrew’s Hospital and the Hampstead Children’s Hospital, he moved to East Grinstead.

Plastic surgery, then, was in its infancy. At the beginning of World War I, in 1914, there had been no plastic surgeons at all in the UK, although the severity of the facial injuries sustained by men fighting saw a number of pioneering surgeons begin to specialise in this emerging field of work. Despite their efforts, by 1939 there were still only four plastic surgeons in the UK. These surgical pioneers, who numbered Harold Gillies and Henry Tonks among them, had a great influence on McIndoe.

McIndoe came to Queen Victoria Hospital with the key members of his operating staff, and inherited a top notch nursing team. The Museum profiles a number of them and I loved reading about their different personalities (brought to life by some great black & white photos) and the compassion they showed in caring for the seriously injured – and traumatised – men in their care. Matron Jackson, for example, saw her remit as extending beyond medical care: “…we went out socially with them and got them out as soon as we could, going down to the pub, going into town. We worked very hard on the psychological aspects”.

For his part, the Hospital’s Chief Anaesthetist, John Hunter, refused to wear a surgical mask or cap for fear of “looking like a continental chef”. Before each operation, Hunter would make a bet with the patient that if he was sick after coming round then “he would buy him a beer”.

During the War McIndoe treated thousands of burns patients, performing up to 17 operations a day. He encouraged both hospital staff and Guinea Pigs (as he called his patients) to observe his surgical procedures. This helped the Guinea Pigs to prepare themselves mentally for what was going to happen to them: particularly important for those men who had to undergo numerous procedures to rebuild their faces and/or hands. Fittingly, the original Allen & Hanbury operating table which McIndoe used throughout the War is on display at the Museum.

McIndoe was a pioneer in so many different ways. At the outbreak of WWII, the universal treatment for burns was tannic acid applied in a gel form known as ‘Tannafax’. This prevented further fluid losses and infection by creating a protective shell over the wound. However, when applied to delicate skin such as eyelids and fingers, it caused the skin to contract, making successful reconstructive surgery difficult. Said shell had to be removed before surgery could take place and McIndoe saw for himself how incredibly painful this was for his patients. He campaigned against the use of tannic acid for burns and by the end of 1940 he had persuaded the RAF and the Ministry of Defence to ban it.

It was Harold Gillies who taught McIndoe the tube pedicle technique: cutting a flap of skin, usually from the chest or leg, and stitching it into a tube which could be ‘walked up’ the body from its original location to the site of a burn injury. By creating this tube, the surgeon maintained the blood supply to the tissue keeping it alive and healthy before it was grafted.

McIndoe went on to refine the procedure into a more effective skin grafting method for facial and hand reconstruction for his ‘Guinea Pigs’. From 1939-45, 4,500 burned Allied aircrew were rescued. More than 80% of them had Airmen’s Burns: deep tissue burns to the hands and/or face, unlike anything surgeons had seen before.

The Museum tells the stories of some of these men – and they make for poignant reading. Tom Gleave, for example, was part of an attack on a German Junkers 88 bomber when he was hit by incendiary ammunition. While he struggled to open the hood of his plane to escape, there was an explosion which shot a burst of flames through him. Amazingly, following treatment by McIndoe, Tom returned to operational duties within a year.

Sandy Saunders suffered 40% burns to his face, legs and hands when his glider stalled, then crashed, during a RAF training flight. McIndoe replaced Sandy’s eyelids, performed a nose graft and made other surgical adjustments to his face. After the War, Sandy trained to be a GP, wanting to “pay back” McIndoe’s kindness.

“Facial reconstruction and plastic surgery were really experimental in those days. He told us that every operation he did was essentially an experiment, which is why we were nicknamed the ‘guinea pigs’…”.

Alan Morgan’s story is particularly moving. A Flight Engineer, Alan was flying a Lancaster bomber on his 21st birthday, wearing the ring his girlfriend, Ella, had given him a few days previously, when his plane was hit. A door blew open, causing the temperature and air pressure to drop: Alan tried to close the door but his hands had become stuck to the frozen metal fuselage. McIndoe tried to save Alan’s fingers, but he lost eight of them to frostbite. The surgeon did manage to create stumps from what was left, which meant Alan maintained some movement.

After the war, Alan was unable to find work because no one would employ him, eventually getting an interview and job by keeping his hands in his pockets. He went on to work as a highly-skilled tool maker and was able to work to precisions of 2/10th of a thousand – the equivalent of a strand of hair. Alan and Ella got married and their son now wears the ring that Ella gave Alan.

These stories are all the more affecting when you consider that many of the Guinea Pigs suffered burns which required them to undergo multiple operations. Some spent up to four years living at the hospital and Ward III was not only their home but the centre of Guinea Pig activities. The Guinea Pig Club had been formed in 1941 as a social support group, its membership open to any members of Allied Aircrew who had undergone at least two operations at the Queen Victoria Hospital for burns or other crash injuries.

On Ward III, McIndoe allowed a barrel of beer, turned a blind eye to practical jokes and encouraged flirting with the nurses. In contrast to the rest of the hospital, Ward III was painted in cheerful greens and pinks and had homely chintz curtains. Ward III also had its own piano, encouraging socialising and singing amongst the men. There was, however, no room for self-pity.

To help with their social rehabilitation, McIndoe appealed to the people of East Grinstead to welcome the disfigured Guinea Pigs into their lives. He encouraged the men to go into town and they soon became a regular sight in the local shops and pubs. As people got to know the Guinea Pigs it undermined the long-held belief that disfigured people should be hidden away. East Grinstead residents went out of their way to accept the Guinea Pigs and this is the reason why the town became known as ‘The Town That Didn’t Stare’.

McIndoe encouraged politicians and celebrities to meet and socialise with the Guinea Pigs as a way of supporting the war effort. Soon, the Guinea Pig members were being invited to film and theatre premieres; over the years they met stars including Clark Gable, Winston Churchill, Dame Vera Lynn, Joyce Grenfell, Tommy Trinder, Max Miller and Max Bygraves.

After the War, the bonds between the men, their friends and families and the medical staff remained strong. Many of the men returned to East Grinstead throughout the 1940s and 1950s for further surgery and continued to socialise. They continued to meet for their annual ‘Lost Weekend’ and enjoyed a busy social calendar until their numbers dwindled and physical frailty prevented them from travelling to East Grinstead. Their last full reunion was held in 2007; today, meetings are more informal and for those who are able to make it.

It’s difficult to put into words what an emotional impact ‘Rebuilding Bodies and Souls’ has. The pioneering work of Archibald McIndoe, the esteem in which he is held by so many people and, above all, the staunch heroics of the Guinea Pigs make this exhibition a humbling experience. More than anything, it’s a salient reminder, in these troubled times, of the debt we owe to those who fought to defend our liberty so that we can enjoy the privileges that we seem to be taking for granted right now. Although this country may seem more divided than I can ever remember seeing it, the example set by the Guinea Pig Club and their inspirational leader, Archie McIndoe, gives me hope that we may, yet, find our way to a kinder and more optimistic place.

As I think you know, I love your often random posts because they are so informative, but this one was also incredibly moving too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, David. For my part, I found learning about Archibald McIndoe and his Guinea Pig Club both humbling and moving.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi. I came across your story whilst researching my family tree today, and am fascinated by how amazing Archibald McIndoe’s pioneering work was, not least because he did a fantastic job of treating my mother at East Grinstead during the war. Unfortunately she has now passed, but I remember het telling me about how she was badly burned at the age of 5, in 1943 or 4, and had lots of surgeries to try and repair her arms, hands and head. He did such a brilliant job that it was hardly noticeable with a little make up. She told me that she remembers being on a ward with all the airmen, who were called guinea pigs, and they called her piglet. She said they were all lovely to her and often gave her their treats. She said that one chap said they could start a juggling double act as they both had opposite hands sown to their thighs!!!. How lovely that through all their terrible life changing injuries, they managed to keep a sense of humour. Testament to Mr McIndoe’s ‘whole body” treatment. She also remembers Vera Lynn visiting and giving her 2 dolls, a lovely story too. I only wish there were photographs of her there, but I have tried, unsuccessfully, to find one, and there doesn’t seem to be any. Thank you for sharing the story, it has enlightened me no end. Nicky.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Nicky, your message has brought tears to my eyes. I had no idea, when I wrote the post about the Guinea Pig Club, that it would be read by someone who has a personal connection to the Guinea Pigs – and such a poignant one, too. How wonderful that your mother was able to share these memories with you – and that she had the good fortune to be treated by Archie McIndoe. Thank you so much for getting in touch – and I wish you the very best of luck in researching your family tree. In terms of photos, have you tried contacting the Museum? It has an extensive photo and book archive that you can search online or in person: https://www.eastgrinsteadmuseum.org.uk/our-collections/

LikeLike

Thank you for replying. Yes, I did email the museum but have not had a response as yet. It’s such a shame that I didn’t really know about the Guinea Pig Club years ago, I never thought much of it all until my mother died 2 years ago, I was writing a eulogy, and I remembered the things she told me about her scars. I didn’t even know the club existed otherwise I would have tried to contact any of them to see if they remembered her. I’m sure there wasn’t many, or any, other 5 year olds on the burns ward !! Thank you again for the story.

Nicky.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fabulous story about your mother.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is an amazing post and very informative. Very very interesting facts about plastic surgery. Thank you for sharing and the history lesson 🌻

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Arnetta: I’m so glad you found the post interesting. I had a fascinating time researching and writing it: the story of Archie McIndoe, his pioneering plastic surgery and his Guinea Pig Club is one that deserves to be shared far and wide.

LikeLike

I have nominated you for the Sunshine Blogger Award. Lyndsey.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh my goodness, Lyndsey: what an honour. Thank you so much! It’s completely unexpected, but very much appreciated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s my pleasure!😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

As has been said, both informative and deeply moving. I knew of McIndoe’s work and his pioneering approach but the personal stories of the men he treated bring home the enormity of what he achieved. Thanks for this humbling post. Let’s hope your closing wish is heard.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I hope so as well, Sandra. Thank you for your lovely comments; I enjoy your writing very much, which makes your feedback all the more special.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an amazing story. McIndoe is a hero.

LikeLiked by 2 people

He most certainly was. Sadly, he died at a young age: he passed away in his sleep aged just 60 years old, in 1960. It’s a testament to his legacy that the Guinea Pig Club continues to this day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Coming tomorrow: The Guinea Pig Club and the Town That Didn’t Stare. […]

LikeLike

What a wonderful reminder of the days of heros who endured so much for our freedoms. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so glad you enjoyed reading it. I found researching and writing this post a humbling experience: it’s difficult to put into words the heroics performed by the generations before us. We are very blessed to enjoy the freedoms that we have.

LikeLike

I have been listening to Dan Carlin’s podcast about WWI called Blueprint for Armageddon. He includes so many personal and touching examples of the heroics that have been so often forgotten. The series is well worth a serious listen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds very interesting and exactly the kind of thing I would enjoy. I will definitely seek it out: thank you for the recommendation.

LikeLike