Through serendipity, I was invited to a lecture on ‘The Making of London’s West End’, having only recently attended a fascinating lecture about The White Slave Trade and the Policing of the Late Victorian West End; how lucky for me that, within a short space of time, I was able to enjoy two talks which complemented each other so well.

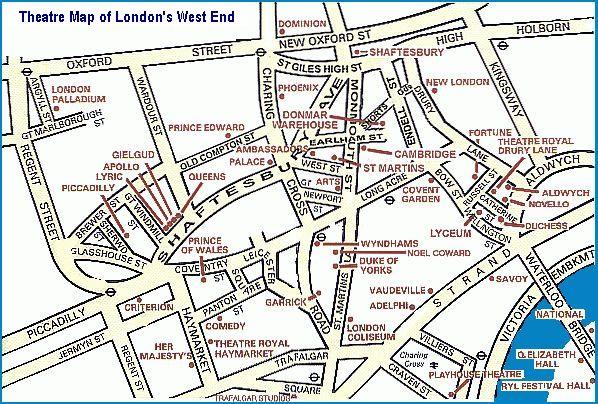

Where, and what, do we mean by the ‘West End’? This famous slice of London once comprised Mayfair and St James, which were found at the west end of town during the 18th century. Within 50 years, however, the concept of the West End as a ‘pleasure district’ was underway, encompassing the area between Bond Street, Oxford Street, Kingsway and the Strand. This swiftly became known as “theatre land”, hosting a huge concentration of theatres unrivalled anywhere other than New York.

A number of deciding factors led to the West End’s creation – and that of the notorious Man About Town. Let’s travel back in time to 1794, when Robert Barker built his Leicester Square Panorama – the first purpose-built panorama in the world. That pocket of London, now more beloved by tourists than by Londoners, was once filled with shops targeting the middle class consumer and is where Prince Albert chose to host the Great Exhibition, before moving it to Hyde Park.

A panorama was a vast painting enhanced by special effects. Spectacular in scope, panoramas focused on great cities, natural landmarks or places of natural beauty – and countless people came to view them. The scale of these paintings was part of their “pleasure”; sadly, few have survived. Their legacy, however, is immense: they influenced theatre set designs and helped turn Leicester Square into a place of spectacle.

Another influencing factor was the opening of the Adelphi Theatre in 1806. I was intrigued to learn that this London landmark was built by the merchant John Scott who wanted to showcase the singing talent of his daughter, Jane. This talented lady also wrote plays, burlesques and parodies, all of which were performed at the Adelphi. The theatre’s opening night was marked by songs, then phantasmagoria (magic lanterns) – a move which anticipated the arrival of cinema.

Theatre, in the early 19th century, was society’s equivalent of TV and was enjoyed by all classes. One particularly big success was ‘Tom and Jerry’, based on the novel ‘Life in London’, much of whose plot centres around young men “slumming it” with the poor. It ran for 100 nights (as opposed to the usual 2-3 performances) and was a pre-cursor to the long-running shows which have become icons in their own right, such as ‘The Mousetrap’. And in case you were wondering, the Tom and Jerry cartoon characters are named after an American soft drink that was named after the play.

The development of Regent Street was another contributing factor to the creation of the West End. Designed by the Prince Regent and John Nash to connect Regent’s Park with Carlton House, its central section was intended to form a luxury shopping centre to rival that of Bond Street. However, its infamous colonnades became associated with prostitution and in 1948 were removed and added to the side of Theatre Royal Drury Lane.

Regent Street was home to a number of elegant French shops, at a time when France was still setting trends in food and fashion – and Regent Street as a whole proved very popular with the Royal Family. So did Piccadilly’s exclusive Burlington Arcade, which to this day is policed by beadles.

From 1850 the West End blossomed, although this process did not happen overnight. A critical problem, would you believe, was a lack of ladies’ lavatories. Well, I say “lack”: in actual fact, there were none. Even in the theatres. It was the rise of the department store, complete with lavatories, which brought about change, together with the innovations I spoke of in my previous post: new streets, improvements in street lighting & cleaning, better local government and improved policing.

Increased railway lines, too, made it much easier for people living outside London to visit the capital (and ladies’ lavatories were, mercifully, built inside new stations like Charing Cross).

What of the individuals who helped shape the West End? You may be surprised to hear that were several highly successful female theatre managers, including Eliza Vestris, who ran the Olympic Theatre, just off the Strand. Cesar Ricks turned The Savoy into the greatest hotel in the world and helped to create the Carlton Hotel on the Haymarket (now sadly gone). And WGR Sprague designed eight theatres, all intended to dazzle the public – especially music halls like the Alhambra Theatre of Variety, with its beautiful minarets.

These music halls boasted surprisingly eclectic bills: a single evening would feature comedies, performing animals and at least two ballets. Ballet flourished in music halls and was loved by the public – due in no small part to the visibility of women’s legs, a rare occurrence in Victorian London.

Arguably, it was at the Gaiety Theatre where musical theatre was invented, by a certain George Edwardes. One of the Gaiety’s biggest attractions was the many pretty girls who performed there, many of whom went on to become big stars and of whom postcards were sold. The theatre’s most celebrated patron was a certain Winston Churchill who, while a Sandhurst officer, bribed his way backstage to procure a signed postcard.

I hadn’t realised that the emergence of grand hotels such as the Savoy coincided with many of the aristocracy selling their London homes and basing themselves in the countryside; if they needed to come to London it was far cheaper to stay in a hotel than to maintain a city residence. Most of those distinguished London houses were knocked down and/or turned into office blocks: planning permission regulations were far less strict then and the Victorians had few qualms about demolishing buildings.

For much of the 19th century, the shops, restaurants and theatres of the West End existed to serve the likes of actor Charles Wyndham, who ruled over the Criterion Theatre for so long (that theatre’s bar was where Dr Watson first heard the name ‘Sherlock Holmes’). Wyndham and his fellow men-about-town would have been all-too-familiar with the brothels for which Haymarket and Panton Street, so innocuous now, were notorious: Haymarket was the 19th century equivalent of Soho, in those days a cosmopolitan area associated with refugees and coffee houses. Your typical man about town went to the theatre of an evening, then caroused with the “harlots” typically found in the West End’s pubs and music halls.

inevitably, the 20th century brought with it many more changes which I hope, in due course, will form the basis of another post. London as a subject continues to intrigue and inspire me: to paraphrase that great man Samuel Pepys, I cannot imagine ever growing tired of it.

I love how you weave these historical stories and landmarks of London into very enjoyable reads Liz. Always enjoy your posts 😊

LikeLiked by 3 people

What a lovely compliment: thank you so much, Carla. I love reading your posts, too: I always learn something from them, and from my other fellow bloggers’ posts – which I think is one of the nicest things about being part of the blogging community.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m also a fan, very much, of the eclectic but so informative posts you write. Subjects I’d often never delve into were it not for following your blog.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That is such a lovely thing to say: thank you. For my part, I love reading your posts – and your recent ones, from Paris, have described the city, and everything it has to offer, beautifully.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Most interesting Liz. We also discovered the French slave trade monument in Nantes. The largest number of French slave trade expeditions departed from Nantes quite some time after the Portuguese indulged in similar events.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I had no idea about that, Elwyn. It just goes to show how much of history is hidden from us; every country has a dark side. I hope you’re enjoying your time in France and are lapping up this unexpected heatwave!

LikeLike

Great post again although sadly unlike the great man Samuel Pepys I am growing a little tired of it, I find myself more in the camp of Samuel Johnson who said, when a man is tired of London he is tired of life. In my defence I must say I am not tired of London and if I were extremely wealthy and had my own chauffeur driven limousine I would visit more often. The surprisingly hot journey I experienced on the tube last night for a friend’s birthday has put me off a visit for the time being. The only thing I can add to your post is the little piece of trivia that the only road in London where you have to drive on the wrong side is the entrance to the Savoy Hotel and Theatre.

LikeLiked by 2 people

London is magnificent in many ways, but I agree that it does not deal very well with heat, particularly the extremes that we’ve experienced recently. I’m lucky in that I take the bus to work, so can sit by an open window during my commute, but my colleagues who use the trains and tubes have had a pretty grim time of it over the past weeks. I thought I was dealing quite well with this hot weather but it must be affecting me more than I thought, as I appear to have mixed up my Samuels!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know the feeling, see video link. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WS_YAKZH3lw

LikeLike

I absolutely love this. How magnificent is Ann Miller? I can only imagine the chaos that would ensue if I attempted to tap dance across my coffee table and on to the back of the sofa.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m already much more familiar with the history of East End London and I’m a great fan of social history and arts & performance, so this was a fascinating read. Thank you for sharing Liz!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you – I’m so pleased you enjoyed it:)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been here and never knew all this! Great information.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So glad you enjoyed the post 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this post, Liz; fascinating stuff 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Liz, you enchant me! I love London. I love theatre. Thanks for your awesome post. Looking forward to reading more. ❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is so kind of you to say: thank you so much. Likewise, I am very much enjoying your posts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such sweetness to enjoy my day with a joyous kindred spirit! STAY LOVELY LIZ! ❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Joyous indeed: thank you 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love reading about the history of London! This was fun and interesting.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much, Jane – I’m really glad you enjoyed the post.

LikeLike

❤️

LikeLike

[…] Every now and then, you discover a restaurant that’s so special you’re loath to share it with anyone else. Zoilo is one such place. I was lucky enough to come across it during a rare weekend shopping trip in the West End and it proved the perfect balm to my sore feet and weary brow (there’s a reason I venture down Oxford Street so infrequently on a Saturday; would that it remained the genteel thoroughfare of the 19th century). […]

LikeLiked by 1 person